Reading intervention is one of the most powerful tools educators have to close literacy gaps and support struggling readers. As students progress through their literacy journey, their needs vary widely—from mastering phonemic awareness to developing reading fluency and comprehension. Aligning strategies with specific skill deficits ensures instruction is both effective and efficient. In this article, we’ll explore how to identify where a student needs support and how to apply targeted, evidence-based interventions across the five essential components of reading tailored to each student’s stage in their literacy development.

The Power of Science

Thanks to research on the science of reading, we now know what students need to truly excel in their literacy achievement. After years of trying to do it all, teachers understand that all students benefit from systematic and explicit phonics instruction. Unfortunately, there is a growing literacy gap that has not recovered since pre-pandemic levels. 2024 NAEP scores revealed that fourth and eighth grade students reached a new low in reading achievement.

Schools are trying to rethink their core literacy curriculum and find ways to close the gap for students who have fallen behind. Formative and summative assessments are also critical to determine exactly where a student is on this journey.

These statistics may sound dire, but knowledge is power. Schools need a solid phonics core curriculum in addition to exposure to authentic text, and one-size solutions often fall short. Teachers must utilize effective, evidence-based reading intervention programs tailored to specific literacy needs. In this age of information, it can still be overwhelming to determine where to begin. This article will provide insights on how effective academic intervention empowers students, uses ongoing assessments, and bridges skills to real reading.

Understanding the Literacy Journey

Teaching reading is never as simple as “teaching reading.” Reading is a critical skill made up of multiple components that all need to come together perfectly for reading to be fluent. It is helpful to break down reading into its five main components: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

- Phonemic awareness is the brain’s ability to manipulate sounds in words, preparing students for the essential skills of blending phonemes for reading and segmenting sounds for spelling.

- Phonics includes the ability to attach graphemes to phonemes (letters to sounds) for both decoding and encoding.

- Fluency is how smoothly text is read aloud, including expression, intonation, and prosody.

- Vocabulary includes the vast web of word meaning knowledge.

- Comprehension is the ability to truly understand what has been read. This includes within and beyond the text itself.

All of these components are critical for reading success. Although students are exposed to all of these elements each year, the skills required for reading success can be arranged in a hierarchy, helping teachers to know where to begin with intervention. Systematic instruction of these skills, layered, flexible, and student-driven, is key to success.

What Makes an Effective Reading Intervention?

A reading intervention includes specialized instruction in reading provided to a student in order to close a learning gap. A reading intervention program is a set of lessons targeting a certain skill.

Reading interventions are developed to target skills within the five components of reading. Strong interventions include evidence-based practices that extend learning beyond the classroom; motivate students to participate using engagement-focused instruction; rely on rich, authentic-text; and use comprehension strategies including vocabulary acquisition. The heart of all reading interventions is the integration of formative assessments to drive instruction, summative assessments to evaluate instruction, and progress monitoring to measure impact along the way.

Matching Intervention to Literacy Needs

In order to know where to begin an intervention, it is essential to use assessment data. A universal screener will help teachers to determine which students are at-risk for reading. Once these students are identified, diagnostic (formative) assessments can be used to target the student’s greatest area of need. This is where intervention should begin. Here is a practical guide for matching intervention to literacy needs.

Phonemic Awareness

Phonemic awareness is the student’s ability to manipulate individual sounds in words. At the beginning of kindergarten, students typically begin to isolate beginning sounds in words, eventually moving to ending and medial sounds. Over the course of the year, students will be able to segment sounds in words with three to four sounds. This is an important pre-spelling skill.

Once students learn their letters, they will be able to attach graphemes (letters) to phonemes (sounds).

Students will also learn to blend sounds to make words. This is a critical pre-reading skill. Once students know their letter sounds, they will be able to view letters in a word and blend the sounds together to read. As students work though kindergarten and into first grade, they will also practice sound manipulation. This is the act of substituting sounds in words. This skill prepares students for word chaining activities, and ultimately prepares their brain for orthographic mapping—the brain’s ability to quickly store and retrieve words, leading to automatic word-recognition.

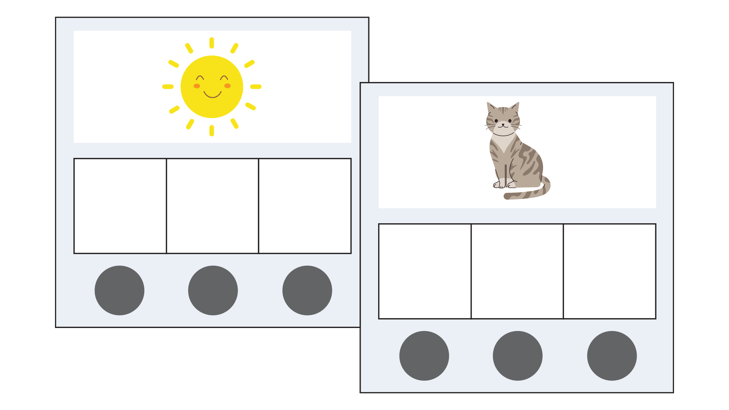

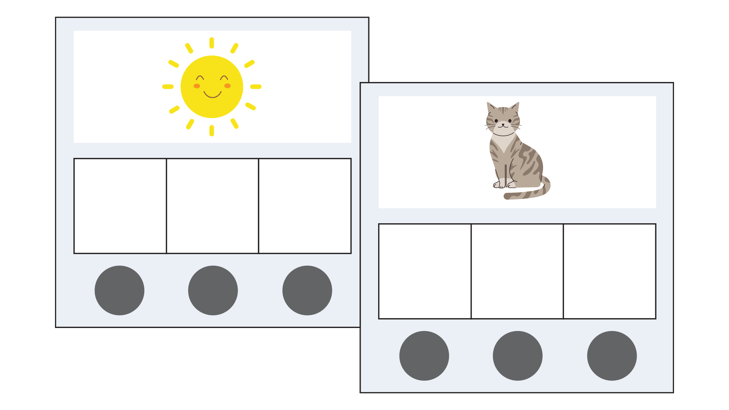

When a student struggles in any area of phonemic awareness, it is vital to provide an academic intervention. For early and emerging readers, learning interventions should be explicit, multi-sensory, and engaging. This may include the use of sound chips, Elkonin/sound boxes, sound matching games, sound isolation games, sorting activities, and “I spy.”

Reading intervention programs should include formative checkpoints. For example, once students are able to isolate beginning sounds, it is appropriate to move on to ending sounds, and then medial sounds. A systematic scope and sequence of hierarchical skills will help teachers understand what skills should be mastered in which order. Phonemic awareness interventions can be quick, targeted, and fun. This early investment in skill-building will support students as they begin to work with letters.

Phonics

Research has shown that phonics instruction is essential for all readers, especially those experiencing difficulty with letter/sound relationships and decoding. Quality phonics instruction must be explicit, sequential instruction that builds transferability. Most phonics programs move very quickly. Every year there is a group of students who seem to master the focus skill effortlessly and apply it in both reading and spelling. There is also a group who require much more time, guided practice, and corrective feedback with each skill. Students at this level may require a phonics intervention.

Formative assessment data using a diagnostic phonics survey will inform teachers as to where to begin. Once this information is analyzed, teachers can group students with similar needs. Phonics instruction is best delivered in an explicit, systematic manner moving from teacher-modeling and practice at the word-level, to guided practice at the sentence and passage level using controlled decodable text. Repeated practice with controlled texts aids students in building automaticity as it promotes a high level of successful reading of pattern words. As students become more comfortable with a given skill, formative assessment data will confirm if it is time to move on to the next skill in the sequence. The goal is always to move towards transferability to authentic texts.

Vocabulary

Students enter kindergarten with vast differences in their vocabulary knowledge, and this starting point can impact them throughout their reading journey. Students with robust vocabularies tend to comprehend text at deeper levels. They can make deeper connections to the text and increase their ever-growing content-knowledge. Students with limited vocabularies will find many roadblocks along the way, and will require more explicit instruction in domain-specific and academic language.

Research shows that teaching vocabulary should be intentional-explicit and situational. A vocabulary intervention will be targeted with intentional strategies using rich texts, morphology instruction, and multiple exposures to high utility academic words. In addition, students must be taught how to unpack word meanings using morphemes, roots, and context to confirm meaning. Vocabulary instruction can be highly engaging for students as they learn to use sophisticated language in conversation, and are empowered to unlock the meaning of words independently.

Reading Comprehension

Reading authentic text with meaning is the ultimate goal of a student’s literacy journey. Scarborough’s Simple View of Reading explains that reading with meaning happens when students are able to decode and have a solid understanding of language. Students with strong decoding skills and a solid foundation of vocabulary will typically be able to comprehend grade-level text; however, some students require explicit instruction. Core instruction should include the development of background knowledge to assist students in their comprehension of complex text. Reading interventions for comprehension should include additional instruction and guided practice with the core skills including making inferences, summarizing, and questioning. Effective methods include strategy modeling, discussion, and scaffolded reading of engaging complex-texts.

Comprehension difficulties can be difficult to pinpoint due to the complex web of skills that lead to accurate and deep understanding. Teachers may wonder if the difficulty was caused by a lack of vocabulary, attention, skill, or background knowledge. A student may also be learning English as a second language. Teachers must be aware of their student’s needs so that the appropriate scaffolds can be used. This may include providing visuals, additional background information, use of a graphic organizer, or active note-taking. Reading comprehension skills open the door for a lifetime of reading success. Students will gain confidence and independence from this essential practice.

Fluency

Reading fluency occurs when students are able to read accurately, with expression, and maintain an appropriate pace and is critical skill that impacts students in multiple ways. Research shows that fluent readers tend to be stronger comprehenders. As educators, we want students to be able to read with ease so that their cognition can focus on the meaning of the text. Reading fluency is more than just words per minute. Students must read the words correctly, know how to adjust their reading based on punctuation, and move beyond word-calling. Fluency is seen as the bridge between phonics and reading comprehension, since automaticity in reading frees up cognitive space for comprehension. All of these skills lead to reading with meaning.

Fluency interventions should include repeated reading with modeling and feedback loops. It is incredibly important for students to hear the text read fluently before practice begins. It would be counterproductive for students to practice repeated readings with text that is too difficult or with words that are unknown. Teachers should develop fluency in the context of meaningful, high-quality text, increasing engagement and promoting transferability beyond the intervention.

How to Choose the Right Reading Intervention Program

There is a reason why Louisa Moats once stated, “Teaching reading is rocket science.” Strong reading interventions actually rewire the brain, and the ability to read opens the world to students in and beyond school. Here are key considerations when selecting the right reading intervention program:

Is it evidence-based and aligned to the components of literacy?

- Many programs claim to be “research-based,” so look at each intervention critically. Who published it? Is it truly grounded in the science of reading?

- Does it include resources for phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency and comprehension? If not, what pieces are missing? What will need to be supplemented?

Does it include embedded progress monitoring?

- Are there progress monitoring probes aligned to the instruction? Does it include guidance on how to measure and report progress?

Are lessons flexible, differentiated, and engaging?

- Flexible—If formative assessments reveal that a student can move on, is there a clear path for moving ahead? If a student requires more time on a skill, are there options for additional practice?

- Differentiated—Oftentimes differentiation is required within an intervention group. Is there guidance for how to scaffold or enrich materials?

- Engaging—Is the material aesthetically pleasing and not-overwhelming? Is it interesting for the grade-level it is meant to support? Is it developmentally appropriate?

Does it promote strategy transfer to independent reading tasks?

- The goal of any good intervention is to not need it forever! Ensure that students are moving towards independence.

Using Assessment to Guide and Adjust Instruction

Reading interventions are most successful when they are part of a data-driven cycle. The diagnostic assessment will reveal the starting focus of the targeted intervention. Progress monitoring will reveal the impact of the instruction which will determine the need for instructional adjustment. This cycle repeats until the student no longer requires intervention.

It is important to use data strategically and to avoid over-assessing. Generally speaking, students receiving Tier 3 interventions are typically progress monitored weekly, while students receiving Tier 2 interventions are often bi-weekly. Diagnostic assessments may be conducted two to three times per year, depending on the need for confirming growth or re-evaluating intervention focus. Universal screeners are typically conducted three times per year. These are not as useful for intervention purposes, but they help to understand how students are performing compared to their peers.

Visible learning techniques boost student motivation and ownership by clearly showing what they are learning, why, and how they are growing. Teachers should openly share and involve students in setting goals. Graphing progress monitoring data provides a visual of their efforts and intervention participation, making goals accessible and highly motivating.

A Real-World Reading Intervention Program in Action

Implementing a successful reading intervention program requires strategy, collaboration, and actionable data. In a school district I work with, we embraced a data-driven cycle to refine our multi-tiered systems of support and to improve student literacy outcomes. Stakeholders—from administrators to classroom teachers—aligned around a shared goal: close reading gaps using targeted, evidence-based interventions.

We anchored our process with three annual data meetings, using universal screening data to identify students in need of Tier 2 or Tier 3 support. As the reading specialist, I partnered with teachers to dig into diagnostic assessments and subtest results, selecting the most effective reading intervention for each student based on skill gaps. We matched each student with appropriate progress monitoring probes and regularly adjusted instruction based on weekly formative data.

We approached Tier 2 as “core and more” and Tier 3 as “core, more, and more”—ensuring that students receiving intensive intervention also had access to high-quality core instruction. Interim check-ins allowed us to evaluate progress monitoring trends, respond in real time, and adjust interventions proactively. This responsive model led to consistent growth, particularly in reading fluency and decoding accuracy.

Most importantly, this system fostered teacher confidence and collaboration. Educators felt empowered, not isolated—supported by a shared understanding of collective responsibility. The case underscores a key takeaway: the most effective reading intervention programs are not only evidence-based but also flexible, data-informed, and embedded in a culture of continuous improvement.

Effective reading intervention is targeted, responsive, and tailored to meet the needs of the student. Interventions can also be highly-engaging through the use of games, rich-texts, goal-tracking, and practice with peers. It is highly encouraged for educators to continually assess students to be able to differentiate meaningfully while inspiring students with rich text and utilizing proven strategies.